UN Claims Mining "Powerful Tool" For Money Laundering

The UN Office on Drugs and Crime's latest report on South-East Asia makes no sense.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has released a new report titled "Inflection Point: Global Implications of Scam Centres, Underground Banking and Illicit Online Marketplaces in Southeast Asia" that appears to be riddled with logical inconsistencies.

In a case study of "clandestine cryptocurrency mining operation in militia-controlled territories of Libya," the UN claims that "illegal crypto mining operations provide organized crime groups with a powerful tool for generating and laundering illicit funds while minimizing detection risks."

According to the UN, these "unauthorized mining farms" often rely on "stolen electricity" while providing "illicit actors with a stream of steady and nearly anonymous revenue."

The UN claims that "this can allow them to mine cryptocurrencies at little

to no cost, creating untraceable digital assets with no direct ties to criminal activities," stating that "illegal crypto mining operations provide organized crime groups with a powerful tool for generating and laundering illicit funds while minimizing detection risks."

First, the point of money laundering is to funnel illicit proceeds through legitimate businesses in order to inject proceeds of crime undetected into the economy. Running funds obtained from illegal operations through another illegal operation cannot serve that purpose by design. Criminals can therefore not "seamlessly introduce dirty money into the financial system by generating seemingly lawful earnings" as claimed by the UN, because the mining activities it describes are themselves unlawful, disqualifying its operations from generating the needed proof of funds.

Citing a report from the Metropolitan Electricity Authority of Thailand on illegal Bitcoin miners, which, of course, is an entirely different country than Libya, the report underscores its claims that such operations often rely on "stolen electricity." But even if Bitcoin was mined with electricity that was entirely free at a all-in hosting cost of 0, one ASIC would generate a mere return of 6556.58 US Dollars over a period of 24 months at a negative value of investment.

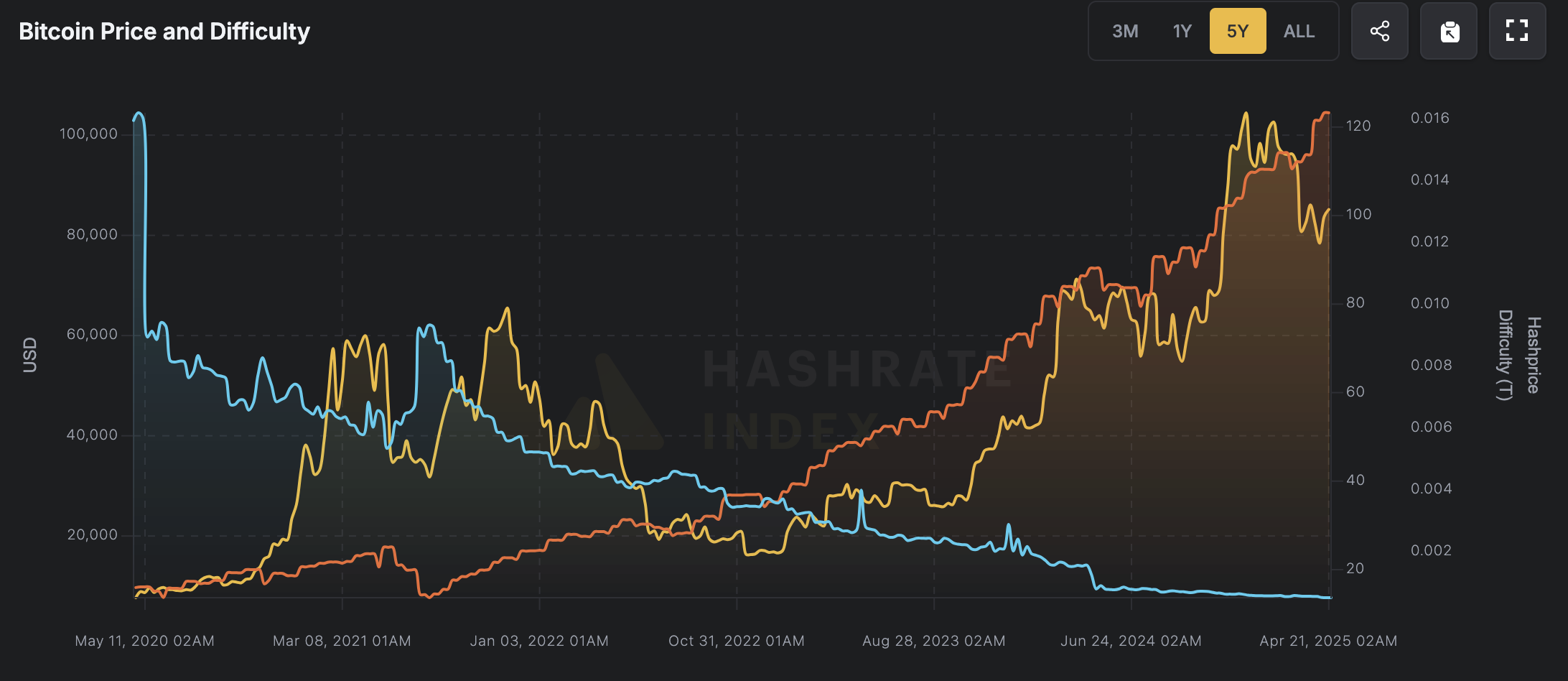

The UN's claim that cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin could be mined at "little to no cost" disregards the fact that ASIC miners are not just expensive in hardware, but also in maintenance, particularly when operated in the Libyan desert, where heat and dust contribute to the machine's wear and tear. With Bitcoin difficulty at all-time highs and hashprice at all-time lows, mining does not seem to fit the category of a "powerful tool" for money laundering, which usually rely on easy and frequent cash flow.

The claim that such operations would "minimize detection risks" is additionally untrue not just because stealing energy from the grid is highly detectable – as seen in Venezuela and Kazakhstan – but also because large mining operations omit significant heat patterns which would require a close-to impossible level of insulation to obfuscate, further denting the UN's argumentation that illegal mining comes "at little to no cost".

The UN notes as much in the beginning of its Libya case study, where it highlights that such activities require "expensive, high-powered mining rigs, large, ventilated facilities, and staff to manage clandestine mining operations."

The UN's claims that "illegal cryptocurrency mining has emerged as a significant concern across the Middle East and Africa, driven by low electricity costs" is then negated by the statement that such operations often rely on "stolen electricity," as the very definition of "stolen" implies that something has not been paid for.

The claim that such operations are "often established in remote areas using off-grid power sources" additionally voids the UN's claims that "illicit mining" is "a direct cause of electricity supply failures [...] depriving essential services and residential areas," as an off-grid mining operation is, by its very definition, not connected to the grid.

One possible explanation for such a claim could be that much of Libya's fuel is traded in black markets following a UN Security Resolution used to order widespread NATO attacks on Col. Gadhaffi's regime, which plunged the country into chaos. Much of this black market fuel, however, is smuggled abroad to be sold at higher prices according to the World Bank, contributing to fuel shortages.

Despite its clearly illogical claims, the UN appears to suggest that such illegal mining operations could be prevented by establishing "anti-money laundering authorities," potentially hinting at the establishment of AML procedures at a mining level.

The UNODC did not respond to requests for comment.

Independent journalism does not finance itself. If you enjoyed this article, please consider making a donation.